Beshear wants ‘scoring criteria,’ Cameron’s appointee prefers flexibility for settlement money

$842 million is coming to Kentucky from opioid settlements with drug companies. How to use it?

BY: MELISSA PATRICK (Kentucky Health News)

This article is republished from Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky.

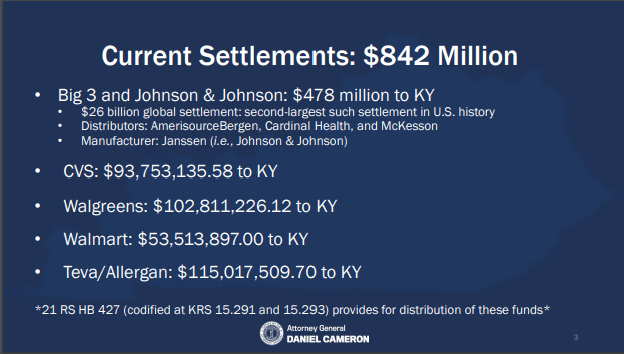

Kentucky’s local and state governments continue to reap more millions from settlements with drug manufacturers and distributors, and are looking for guidance on how to spend the money to provide relief from the opioid epidemic, as the settlements require.The state is getting $842 million, half of which will be allocated by the state Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, with the other half going to cities and counties. Funds are to be disbursed annually, on various schedules, through 2038.

The head of the commission, appointed by Attorney General Daniel Cameron, envisions a practical, strategic, “flexible and dynamic” process. Gov. Andy Beshear and one of his appointees who serves on the commission want firmer guidelines and a scoring system for grant applications.

At the commission’s Jan. 10 meeting, its treatment and recovery subcommittee set the calendar to start making recommendations for the grant awards, and some members said they need formal guidelines, such as scoring rubrics.

One member said it would be important for the group as a whole to be working from the same guidance. Another said such guidance would allow for transparency and consistency in the selection process.

“We need some common themes from the other groups, as well as ours,” said subcommittee member Van Ingram, director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy. “I think we need that before we move forward, so, you know, nobody’s rubber-stamping everything that comes through or nobody’s denying everything that comes through; that we have some common themes we want to look at.”

The next treatment and recovery subcommittee meeting is Feb. 7. Ingram said, “If we don’t have the guidance before Feb. 7 or on Feb. 7, I don’t think we need to be making any decisions. We can discuss. We can look at. But . . . we don’t want to make decisions and then the guidance come later.”

Ingram works for Beshear, a Democrat who is seeking re-election. One of the Republicans running to unseat Beshear is Cameron, who named lawyer Bryan Hubbard chair and executive director of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission.

Hubbard was asked Jan. 19 if the guidance Ingram wanted would be forthcoming. He said, “This is not a process by which we can use strict, academically developed, rigid rubrics to assess the viability of a project. We’ve got to think practically, strategically. And we’ve got to be able to recognize what is going on, on the ground, so that we can deliver the necessary resources to advise good work that’s being done. The application process that we’ve come up with gives us the due-diligence tools to ensure we have competent qualified organizations who can participate, and we aim to resource as many of them as well possibly can.”

Meanwhile, Kentucky Health News asked Beshear at his regular weekly news conference if he shared Ingram’s concerns, and he said he did. “Certainly any process where there’s an application for government funds, has to have guidelines, has to have scoring criteria,” he said, adding later, “That is a great concern that they have taken all of these applications without giving organizations . . . the scoring criteria that will be used. So my hope is that we’ll see some major changes.”

Beshear alluded to the election: “This isn’t about me or anybody else in office; this is about wanting to make sure that this money, which is blood money, is used the right way, is used the smart way. And if they don’t come up with criteria, how are they going to tell all the amazing organizations that there might not be enough funding for in this round why? . . . They’re going to need an explanation about why one thing was funded and another wasn’t early on.”

Cameron’s communications director, Krista Buckel, said regulations unanimously approved by the commission and signed by Beshear outline how it will review the grant applications.

“The regulations . . . clearly outline factors for the commission to use in reviewing grant applications,” Buckel said. “These guidelines provide the flexibility necessary for the commission to strategically and adeptly respond to the opioid crisis.”

Hubbard told the Health and Senate Health Services committees Jan. 19 that the commission had received 32 completed grant applications and that 231 more are in progress. He said the total asked by the completed applications is $63.6 million.

Local officials also seek guidance

At the Jan. 17 Woodford County Agency for Substance Abuse Policy meeting, County Judge-Executive James Kay told Hubbard that the county and its two cities would like a “free blessing” from the commission saying that a program they are considering falls within the law for spending the settlement money.

“I can tell you already that we’ve already had ideas that people( say), ‘I don’t know if that fits the statute’,” Kay said.

Kentucky League of Cities will be handling questions for the cities and Kentucky Association of Counties will be handling questions from the counties. They would, in turn, contact us.

– Alison Chavies, executive staff advisory, Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission

Hubbard told Kay, “Insofar as that’s an idea that your fellow judge-executives would be receptive to, we would love to assist in any way you think is helpful.”

A few days later, Hubbard told Kentucky Health News, “We want to be supportive without being dictatorial. And insofar as there is anyone within local leadership across the state that wants us to bless anything, it’s not a necessity, but we’re happy to do it with him.”

Alison Chavies, Hubbard’s executive staff advisor, told KHN that all programs and projects using opioid-settlement money must fall within existing statutes and regulations, which are strictly bound to opioid-use disorder or co-occurring substance-use disorder or mental-health issues. Further, she said in an e-mail, “Kentucky League of Cities will be handling questions for the cities and Kentucky Association of Counties will be handling questions from the counties. They would, in turn, contact us.”

Asked if the commission is figuring out things as they go along, Hubbard said, “This is an entrepreneurial endeavor within the framework of government. And we are very much engaged in an entrepreneurial exercise in which we have to be flexible and dynamic.”

Latest town hall focuses on high overdose rates of Black Kentuckians

Hubbard told the health committees that in 2021 the overdose death rate was higher among Black Kentuckians than among white Kentuckians for the first time.

“Those deaths are almost exclusively driven by fentanyl, fentanyl poisoning,” Hubbard said. “That began to really show up in state statistics in 2017 and the trend line is a sharp trend line upward. And it is something that we have got to get our hands around and drive awareness of.”

In partnership with Lexington Councilwoman Denise Gray, the commission held its latest town hall at the Consolidated Baptist Church Jan. 17 to address the growing crisis of opioid overdoses in the Black community, Grason Passmore reports for WKYT.

The commission heard from doctors who treat people with substance-use disorders and people who had lost loved ones to the disease.

“When you come into the clinic as someone who is addicted to opioids, there’s already a stigma that you’re trying to get over on someone. We have to get rid of that stigma,” said Quentin Moore, a nurse practitioner.

He added, “Within the Black community we don’t see us as having a problem. Even though somebody just took a pill their aunt was prescribed. They just took the pill because they had back pain. Then they went back again. Then again. And after that, they just can’t stop going back.”

Hubbard told the health committees that common themes in the 11 town hall meetings have been the need for increased prevention programs for youth, creation of recovery support programs, recovery housing, transportation, second-chance employment, expungement of criminal records, acute-phase treatment with seamless transitions to treatment, and addressing the stigma that plagues this disease.

“In our town-hall meetings, it is very clear that Kentuckians wish for those of us who hold public trust to understand the depth and just the immense dimension of pain that exists in the state, that has been produced by this epidemic,” Hubbard said. “We are losing a small town a year and have been for at least a decade.”

Recommended Posts

Kamala Harris needs a VP candidate. Could a governor fit the bill?

Fri, July 26, 2024

After cyber-attack on Jefferson County Clerk, Fayette counterpart discusses precautions

Fri, July 26, 2024

An eastern Kentucky animal shelter is swelling this summer

Fri, July 26, 2024