Settled: The mystery surrounding the 1881 death of Lexington police captain Neale Hendricks

Lexington, Ky., Monday, August 1, 1881

About half past 3 o’clock, policeman Neale Hendricks entered the Short Line Saloon on Water Street. The saloon, which was kept by Charles H Steele, sat “nearly opposite the Watch House,” according to the Lexington Daily Transcript’s reporting at the time.

Hendricks, who was a Captain on the force, heard a disturbance at the saloon from his position at the watch house and headed over with two other officers to check it out. Water Street was a bustling commercial center at the time. Its proximity to the railroad, market, and courthouse made it a popular destination for all walks of life.

Nestled right in the middle of downtown, there were industrial works, restaurants, hotels, 20 saloons (at least), a candy kitchen, and more on the street, where the LexTran Transit Center sits today. Water Street was shortened in the modern era, when the railroad tracks that ran down the middle of it no longer served a purpose.

McCarthy’s Irish Pub is a decent modern day reference point for where Short Line Saloon was located, as the best guess for the historical location is now occupied by, you guessed it, a parking garage.

There had indeed been a disturbance at the Short Line Saloon that afternoon, but it had settled by the time Captain Hendricks entered the building. The other two officers headed back to the station. Hendricks walked a few steps into the bar and peered through the back door to the yard, where a crowd had gathered. Tom Berry was sitting on the ground, getting a cut on his head washed out by Watt Lusby. Lusby’s brother Letcher, the bartender, had hit Berry on the head with a glass for causing trouble in the saloon. This was not particularly unusual for a Monday afternoon on Water Street in 1881. As Hendricks approached the back door, he spotted John Small, whom he’d been looking for. He also spotted Charle Steele.

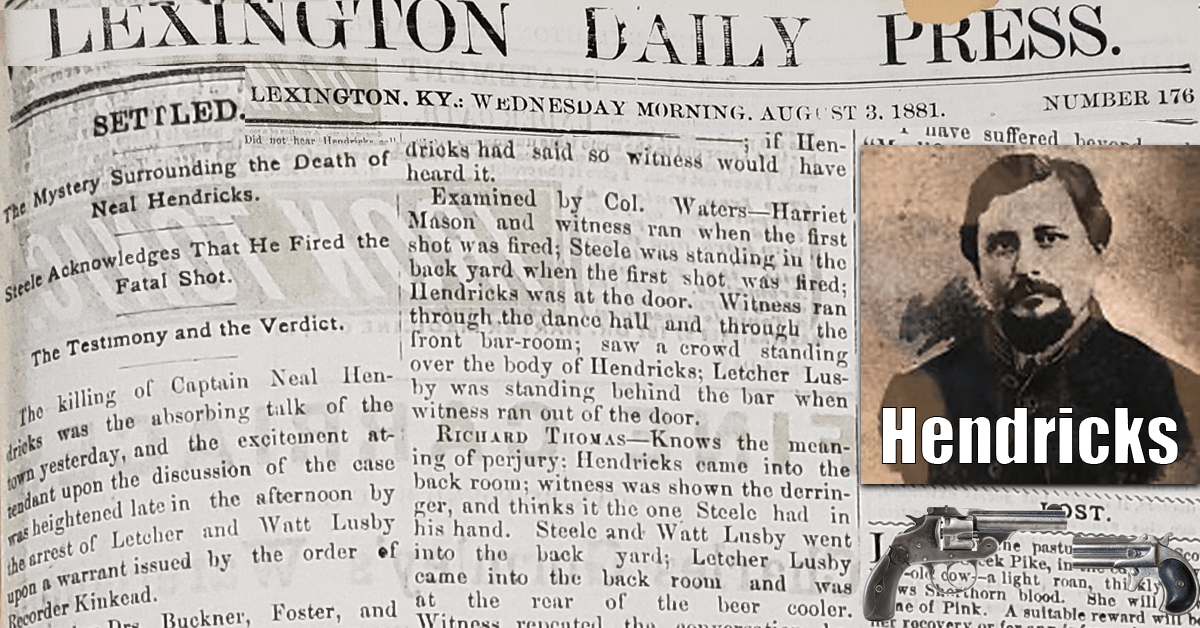

Charles Steele and Neale Hendricks were not strangers. They had served together in the Confederate Army, Second Kentucky Infantry, during the Civil War. Both were described as “men of great courage,” by the Louisville Courier Journal in their reporting at the time. Steele was also described as having a “rather excitable disposition,” while it was said Hendricks “did not know what it was to fear anybody.”

Hendricks and Steele stared each other down. They hadn’t been friendly lately. Steele ran a lottery and a few other hustles on the side, and he suspected Captain Hendricks was the cause of some recent indictments against him. On top of that, Hendricks had a pistol of his that he wanted back. At trial, Steele’s acquaintance, J.R. Jewell, testified Steele told him he planned to take the pistol back, because Hendricks, who had killed two men (one white and one black) since he’d been on the police force, “might be mean enough to shoot him with his own pistol.” Jewell also testified that Steele, who was very drunk at the time, told him that “perhaps some time he might get a chance, and if he did, he intended to lay him out or stretch him out.”

Steele would get his chance.

Lexington City Directories Collection, University of Kentucky Libraries.

Hendricks pointed at John Small and said he’d been looking for him. “I wanna get a hold of you, you damn son of a bitch,” is what Watt Lusby testified Hendricks said to Small.

Small, who was black, said he did not want to go anywhere with the mean ex-Confederate cop. It’s worth noting that several witnesses to the confrontation reported that there were only a handful of white people in the crowded saloon that day, besides the Steele and the Lusbys. There was a dance planned at the saloon that day, so it’s not clear if Short Line Saloon catered to a predominantly black clientele, or if that event specifically drew the mostly black crowd that day. (Lexington was about 55% white at the time.)

Steele intervened and asked Hendricks if he had a warrant, saying Small had done nothing wrong. When Hendricks could not produce a warrant, Steele told him he couldn’t take Small without one.

“Yes I will, and I will take you too, you cowardly little puppy,” Hendricks yelled, according to multiple witnesses at trial.

Steele howled back that Hendricks was a “god damn liar.”

Captain Hendricks did what any self-respecting 1881 cop would do in that situation: he drew his service revolver and shot Steele in the face. Watt Lusby, whose brother Letcher was tending bar, hollered out that he didn’t want any fuss inside the saloon and attempted to restrain Hendricks before he fired.

Guns weren’t as reliable in 1881 as they are now. Hendricks’ shot grazed Steele’s left hand before hitting his head, “the ball glancing around and not penetrating the skull,” according to the Daily Transcript’s reporting. Wounded, but still standing, Steele lurched forward with his head bleeding. “You called me a cowardly son of a bitch, did you?!”

At the end of it, Captain Hendricks’s skull was reportedly so shattered, medical examiners “were able to lift the top of his skull without the aid of a saw” during the autopsy.

August 2, 1881 – Witness testimony leads to new arrests

Charles Steele was taken to Lexington City Jail. The next day, after a court hearing, the brothers Watt and Letcher Lusby were arrested on warrants. According to the Lexington Daily Press, their arrest heightened discussion of the case, which was already “absorbing the talk of the town.”

Charles Steele wore the signs of his two gunshot wounds, sporting a bandage on his forehead and his arm in a sling, when he appeared in court the next day, according to the Courier Journal.

At 10 a.m. on Tuesday, August 2, 1881, Richard Thomas testified to a Coroner’s Jury (similar to a grand jury) that he’d seen Steele run from behind the bar to the backyard with a Derringer to break up a fight before Hendricks arrived. He thought the first shot was from Hendricks’s pistol, but said he also saw Watt Lusby with something in his hand when he was struggling with Hendricks. He testified that he heard someone say Lusby fired the third shot, then heard someone else say to him to “keep his damn mouth shut or he would get his head knocked off.” Thomas stated that he did not want to testify against the Lusbys and would skip town if he were the only witness.

Recorder Kinkead adjourned until 7:30 p.m. at that time, so medical examiners could take another look at Hendricks’s remains and warrants could be issued for the Lusbys. The Courier Journal, who declined to go into particulars of the day’s testimony due to “so many conflicting accounts given by witnesses,” noted that Thomas was also arrested at this time, to keep him from skipping town.

At 8 p.m., Stella Hardy, who fried fish at the bar, testified she saw Hendricks pull his pistol. By the time she heard the first shot, she had already jumped the fence, though, so couldn’t say who had fired. She said Steele had been holding a rusty pistol that “only shoots once” when he went to break up the initial fight.

Annie Smith was in the dance room and heard the shooting. She went to go have a look and saw Hendricks standing with Steele facing him. She testified she saw Steele had blood on his face. He yelled, “you called me a cowardly son of a bitch, did you?” before pointing a pistol at Hendricks’s head and firing.

Smith said that both Lusby brothers and others were “immediately back of Hendricks,” who fell when Steele shot him. She heard only two shots.

Other witnesses confirmed the words exchanged between Hendricks and Steele, that Steele had a Derringer in his hand, and that Hendricks fired the first shot.

Richard Thomas came back and testified that he thought the first shot was fired “in the tussle between Watt Lusby and Hendricks,” with the second shot being fired by Steele. He added that Letcher Lusby was in the back room at the rear of the beer cooler.

While multiple witnesses said they had seen Steele fire a Derringer at Hendricks, striking him in the face, three physicians determined the cause of death to be a point blank shot to the back of the skull. This determination was made based upon a powder burn on the back of Hendricks’s head and a .32 Short bullet that was recovered from his brain. The .32 Short is smaller than the .41 Short load used by a Derringer.

Also noteworthy: It now appeared that Steele had killed Hendricks with his own service revolver. It was an ironic twist for the man who feared Captain Hendricks “might be mean enough to shoot him with his own pistol.”

Steele would confirm to one of the doctors that this was indeed the case, telling him, “he and Hendricks were scuffling on the floor, and that he fired the shot when his hand was around Hendricks’s neck,” according to the Lexington Daily Press. Following this statement, the decision was made by the Coroner’s Jury that there was enough evidence to proceed with the trial.

Hendricks was buried Tuesday, as well. Lexington Police officers honored him by forming a committee to pass a resolution that honored his courage, saying “fear found no lodgment in his breast.” His funeral was attended by “a great number of ex-Confederate soldiers who served with him during the war,” according to The Courier Journal. (Lexington papers did not report this detail.)

August 3, 1881 – The Commonwealth V. Charles Steele

With the Coroner’s Jury having found enough evidence to proceed, the next step in Steele and the Lusbys’ process was what was called a preliminary examination at the time. Similar to a preliminary hearing in the modern system, a preliminary examination would determine whether or not there was enough evidence to try Steele and the Lusbys for murder. If there was found to be sufficient evidence, they would be held in jail pending a full jury trial. Otherwise, their charges would be dismissed and they would be released.

Dr G.D. Buckner testified and confirmed it was a .32 Short to the back of the head that killed Hendricks. Additionally, Hendricks was shot with a Derringer above the right eye (the bullet bounced off his forehead) and he sustained a contusion on the left eye that was caused by a “violent blow.”

Buckner testified that nothing about Hendrick’s clothes indicated a scuffle and there were no scratches on his neck or bruises on his back or chest. He said a man standing in front of Hendricks could not have fired the fatal shot. The shot’s directions was “forward, downward, and a little inward,” and in his opinion it would’ve been impossible to reach around and fire it from the front.

E.M. Garrett, a policeman, had responded to the disturbance at the saloon alongside Hendricks, but left when they found it already quieted. He testified he’d just made it back across the street to the station when he heard the first shot. He ran back, and the last shot was fired as he got into the door. He didn’t see Watt Lusby anywhere, only Hendricks, Steele, and a Mr. Wright. Hendricks’s pistol was about three feet from the cop’s hand, he testified. His head was lying towards the beer cooler in the center of the room. Steele was four or five feet from Hendricks’s pistol.

Garret saw blood on Steele’s face and hands, “God damn him, he shot me first, but I got the best of him, though,” he told Garrett. Steele told Garret the now confirmed story of Hendricks trying to take a black man without a warrant before drawing his pistol and shooting Steele.

Charles Mills, a gunsmith, testified that he examined Hendricks’s pistol and it was his opinion that it had not been fired. The gun was missing one round when showed to him, but was in such bad condition it would not revolve. There was rust in the barrel and chamber and there was no powder dirt in the barrel. Normally, a recently discharged weapon would have powder blacking the cylinder and barrel. He noted that the rust could have accumulated in only a few hours in the conditions, though.

John Shannon testified that he found Hendricks’s pistol in the hands of Letcher Lusby, who was fiddling with it, seeming to try and make it revolve. Shannon told him not to fool with it. Lusby put it back on the shelf behind the bar.

Policeman M.T. Hayes testified that Steele was straddling Hendricks as he entered the saloon, Hendricks flat on his back. He saw Hendricks’s pistol on the floor back and to the left of him when he walked in. He said Hendricks’s pistol was not a good one; they had once tried to kill a dog with it, but it snapped and would not go off.

Nat Williams, Hendricks’s brother in law, got into the saloon before he died. He saw Letcher Lusby behind the bar with Hendricks’s pistol and asked him if there were any loads out. Lusby said one was out. Then he picked up the smaller Derringer and said there was one out of that, too. He told Williams he didn’t see what happened because he was hiding behind the bar.

Richard Thomas, who’d been arrested and compelled to testify, relayed the same version of his story as before. He said Watt Lusby had hold of Hendricks and appeared to have something in his hand. He recognized the Derringer and Hendricks’s pistol, but said he also thought he remembered seeing a third pistol, similar to the one Hendricks had, on the floor.

Thomas testified he saw a puff of smoke rise up from the area of Watt Lusby and Hendricks’s hands when the first shot was fired, but could not be sure it was from Hendricks’s pistol. Lusby was grabbing Hendricks’s wrist at the time. He said Steele then stepped forward with the Derringer. He did not see Hendricks turn around. When Steele fired, Lusby let go of Hendricks. He saw Hendricks stagger back and his pistol fall to the floor. Both Lusbys were behind the counter when he ran out. He heard only two shots and said he was one of the last men to leave.

Thomas went back in after the shooting and saw both pistols lying on the floor. Neither Lusby was picking up pistols at that point, but he saw Letcher in the room. By the time policeman Ben McMurtry made it back across the street, he saw neither pistol lying on the floor.

John Berry said he was one of the only white patrons in the saloon at the time. He heard two shots total. He never saw a pistol in Watt Lusby’s hands and said Lusby tried to get out of the way after the first shot was fired. He said he thought Hendricks’s pistol “went off” because he didn’t think anyone else had a pistol out there, and he heard someone yell, “There, he’s done shot Mr Steele.” After that, he said he saw Steele draw his own pistol and “crack loose” at Hendricks.

At this point, the prosecution announced they had another witness, but they could not testify until tomorrow morning. They said this witness could prove Watt Lusby’s connection to the crime. They did not give his name. The charges against Letcher Lusby were dismissed at this time, and the preliminary examination adjourned until the next morning.

August 4, 1881 – The Judgment

The prosecution’s surprise witness was a dud, to put it lightly. Henry Allen repeated a similar story as most of the other witnesses. He said he saw one of the Lusbys in the room, but was not sure which one it was. He eventually identified Letcher, whose charges had already been dropped, as the one he saw. It’s not clear if Allen was the sensationalized witness prosecutors were referring to the day before, or if that individual had already skipped town. Another possibility is that overnight Allen had been intimidated to keep his mouth shut.

After Allen testified, the defense moved to dismiss the charges against Watt Lusby and Charles Steele. Kinkead agreed to dismiss charges against Lusby, whose testimony he desired to hear.

Watt Lusby’s testimony

Lusby testified that he’d been at the saloon all day and had been there often, as his brother was frequently hired there. He was in the yard washing a man’s cut head, when he saw Hendricks at the back door. Hendricks said he wanted John Small, but Steele said he could not take him without a warrant. Hendricks replied that he would take him if he wanted to and he would take Steele if he wanted to. He added: “More than that, you are a damn cowardly son of a bitch.”

At that, Hendricks drew his pistol. Lusby rushed by Hendricks and grabbed his pistol by the muzzle, then the pistol went off. Lusby said he crawled on all fours to behind the counter and saw no more of the shooting. Letcher Lusby had been tending bar when he went into the backyard and was there when he returned. He said the Derringer was kept behind the bar after the shooting, and not removed until taken by the Coroner.

Letcher Lusby’s testimony

Lether Lusby was behind the counter when the shooting started and did not leave the counter until after the shooting was done. He heard only one shot. He examined Hendricks’s pistol after the incident and said it would revolve “as good as anybody’s,” and turned it two or three times.

Walter Wright testified that he was the one who picked up Hendricks’s pistol and placed it behind the counter. He gave Watt Lusby the Derringer to give to the Coroner. Strangely, he also testified that he had no recollection of picking up the Derringer, but realized he was holding it as he was leaving. He did not examine either gun. Another witness said he saw Letcher Lusby either loading or revolving Hendricks’s pistol behind the counter after the shooting.

Recorder Kinkead’s judgment

Recorder Kinkead, who presided over the preliminary examination, dismissed the murder charge against Charles Steele. The announcement was met with applause in the courtroom.

In his judgment, Kinkead noted that Hendricks called Steele a “cowardly little puppy, and accompanied this opprobrious expression by instantly drawing his pistol and presenting it.” Kinkead noted that Mills and Buckner did not think Hendricks’s pistol had been fired, while “every eye-witness of the transaction says that Hendricks immediately fired, or that at least smoke was seen to curl around his hand which contained the pistol, and which was then held by Watt Lusby.”

He continued:

Be this as it may, Captain Hendricks certainly drew his pistol the instant he employed the expression above referred to, and the defendant, Steele, while in the yard, quickly advanced to the door, which was one step from the ground, placed his knee upon the sill, and fired a shot from a breech-loading derringer at Hendricks who was within the room.

Recorder Kinkead’s judgment. (Aug. 6, 1881 Lexington Daily Press)

It is further in proof that Captain Hendricks was a man of desperate courage; that this fact was recognized by this community, and known to none as such, probably, better than the defendant.

This, though, was not a contest between a policeman on the one side, in the discharge of his official duty, and a citizen attempting to interfere and prevent the execution of it, but purely a personal difficulty between two citizens, in which one certainly employed the most offensive language, drew a pistol, and under the proof in the case, fired it.

If, therefore, the doctrine of apparent necessity ever existed, it is clear to the mind of the Court that in this case, and at this particular juncture it arose.

To a reasonable man in the defendant’s position, it must have been clear to him that Hendricks intended, then and there, to take his life or inflict upon him great bodily harm, and that it was necessary for him to shoot in order to protect his own life.

Downtown Lexington’s last standing Confederate monument

“This, though, was not a contest between a policeman on the one side, in the discharge of his official duty, and a citizen attempting to interfere and prevent the execution of it, but purely a personal difficulty between two citizens, in which one certainly employed the most offensive language, drew a pistol, and under the proof in the case, fired it.”

Recorder Kinkead’s judgment clearly states that Captain Cornelius Neale Hendricks was not killed in the discharge of his official duties as a police officer. He was, in fact, killed in a “purely personal difficulty.” Nevertheless, Hendricks is still honored on the Fayette County Peace Officer’s Memorial monument in Downtown Lexington. The Confederate statues in downtown were previously removed after public outcry, making Hendricks’s memorial site the last remaining monument to a Confederate soldier in downtown Lexington.

This article was compiled using primary sources found at the Lexington Public Library’s Kentucky Room. Hendricks’s first name is spelled as “Neale,” “Neal,” and/or “Niel” in various newspaper reports, though his given name was Cornelius. It has been reported in other places online that Hendricks had once been Chief of Police. The author could find no evidence to support this claim in his research.

Courier Journal Reporting on the case

Lexington newspaper reporting

Recommended Posts

Lexington City Council to consider $400,000 aid for homeless families with schoolchildren

Fri, March 1, 2024

Bills aim to stop people from coming to Ky. to have Medicaid pay for addiction treatment; programs could have to get them home

Mon, February 26, 2024

How Will Lexington’s Economy Grow Over the Next Two Years?

Mon, February 26, 2024